Housing Policy x Climate Policy

Why We Need Solutions That Solve Both

April 8, 2020

Rising vehicle emissions threaten California' climate goals

California's climate leadership is at risk. While the state met is 2020 emissions target of 431 million metric tons of CO2 equivalent (MMTCO2e) 4 years early in 2016, this process has largely been negated by the expansion of car traffic in cities and on freeways.

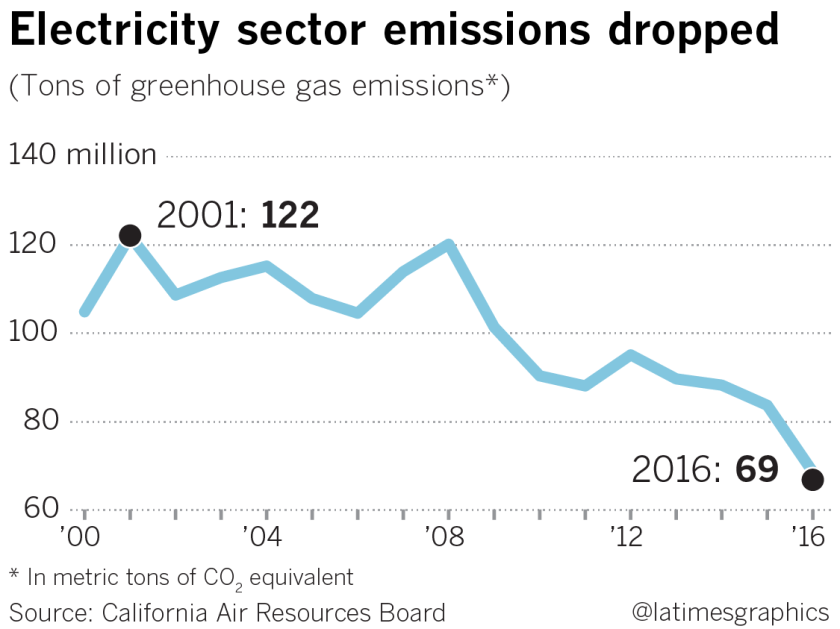

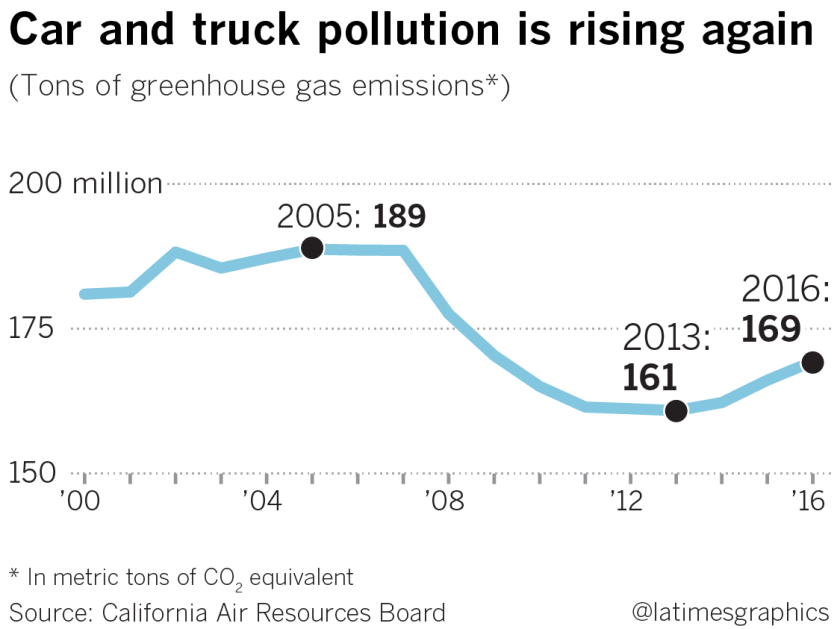

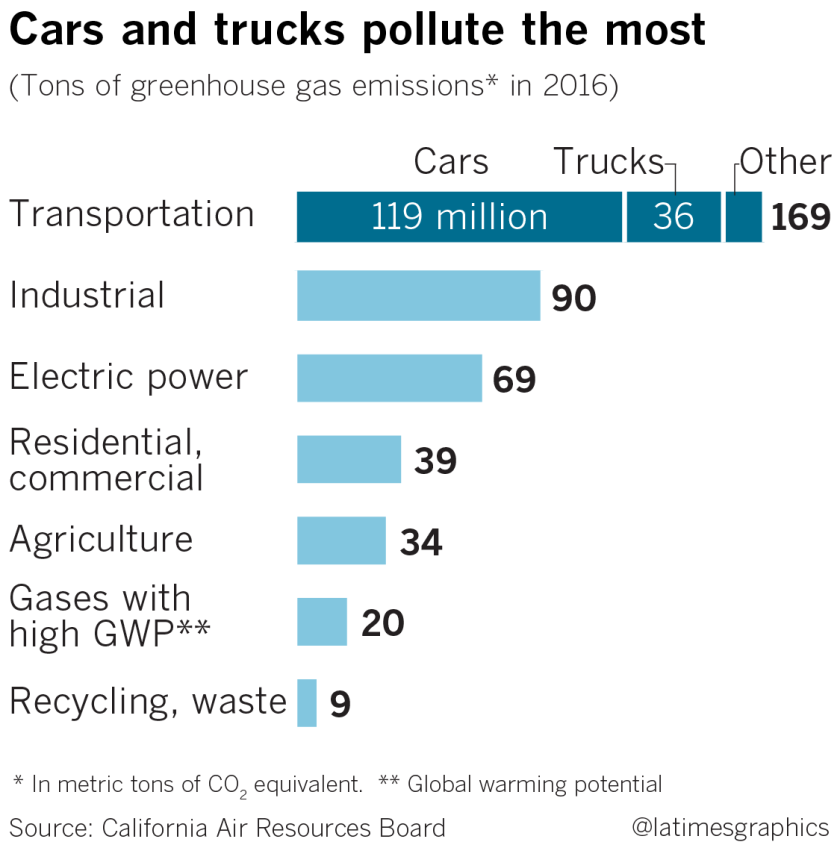

Reduction in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions was primarily due to a growth in renewable energy, specifically an increase in solar and wind power as well as rooftop solar installations on residential buildings. Nevertheless, as of 2013, car and truck pollution is on the rise, which puts California at risk of not achieving the necessary GHG reductions needed to meet the additional 40% mandate for 2030. Around 40% of GHG emissions in California are from the transportation sector, and this amount is steadily increasing.

“The deep reductions from electric power generation are compensation for lackluster performance in other sectors of the economy, including an uptick in the transportation sector.” –Alex Johnson, NRDC

So why the uptick? The rise in vehicle emissions is due to a combination of a growing economy, consumer preference for roomier, less efficient vehicles, a slower-than anticipated transition to electric models, and an increase in single-occupancy car use as of 2012. With more people and more cars, more miles are being driven.

A quick aside to consider is how electrification fits in. Ultimately, while we do need to accelerate the electrification of vehicles, it is not enough as the process will not happen fast enough to solve the problem. According to Nicole Dolney of the California Air Resources Board, “Increases in fuel efficiency are being outpaced by the amount of driving.”

The increasing number of super-commuters

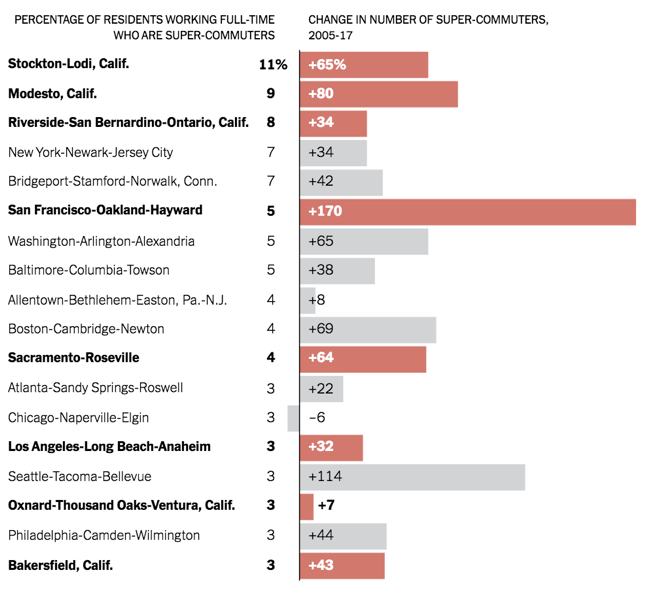

A large contributing factor for the increase in driving is evident in the influx of super-commuters, or the number of residents working full-time that spend 90 minutes or more getting to their jobs. Nationally, 72% of super-commuters drive. 8 out of 20 of the top 100 largest metropolitan areas in the United States are in California. And specifically San Francisco has seen the most growth in the proportion of super-commuters with an increase in 170% since 2005.

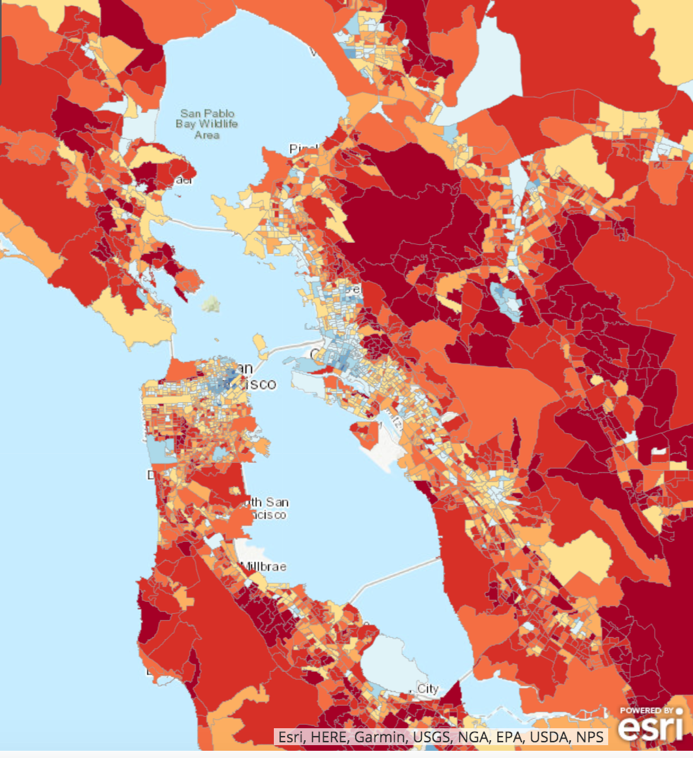

The number of super-commuters is rising because job centers and cities have de facto bans on apartment buildings in areas zoned for single-family homes. Instead, workers have to “drive till they qualify”, or drive until they reach housing that they can afford. People who are priced out of one area move farther away, which increases sprawl and clogs freeways, ultimately increasing GHG emissions. Between 2005 and 2016, there has been an increase of 3.2 million cars on the road in California. This trend is an indication of the low supply of housing, especially affordable housing in job-rich communities.

Top 20 US metropolitan areas with highest proportion of super-commuters

This is truly a sign of inequality. As housing near jobs and transit become increasingly expensive, low-income and working-class people are forced to live further away from where they work. The abundant opportunities, services, and other neighborhood amenities within cities are walled off and only available to those who can afford them. Low-density, single-family home zoning effectively bans economically diverse communities.

To solve the climate crisis, we need to solve the housing crisis.

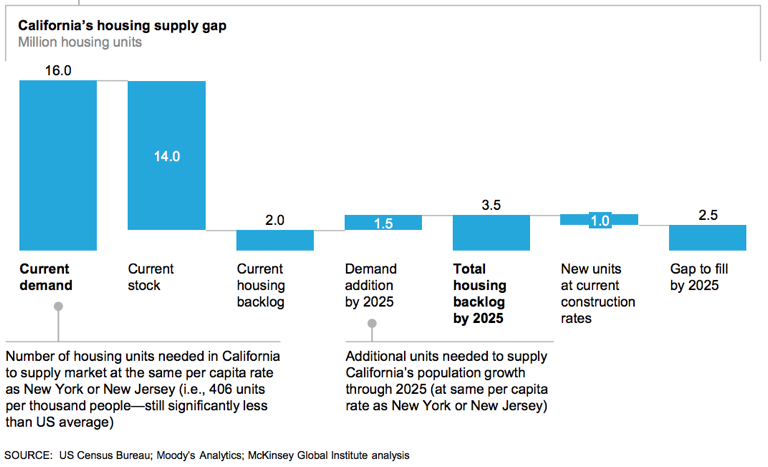

California is short 3.5 million homes. We need significant changes to how communities and transportation systems are planned, funded, and built. By examining the average California carbon footprint in 2010, with an average of 45 tCO2e, 1/3 is comprised of transportation uses, specifically gasoline. A study by the Renewable and Appropriate Energy Laboratory (RAEL) found that infill housing can reduce GHG pollution more effectively than other options such as energy efficiency or shift in consumptions in coastal California cities. Infill housing, or urban infill, is when 75% of a site’s perimeter is already developed or located near high-quality public transportation or a job-rich area. Urban infill is really a solution and an opportunity for carbon footprint abatement.

California's carbon footprint in 2010

In-progress solutions around the Bay Area and the current policy landscape

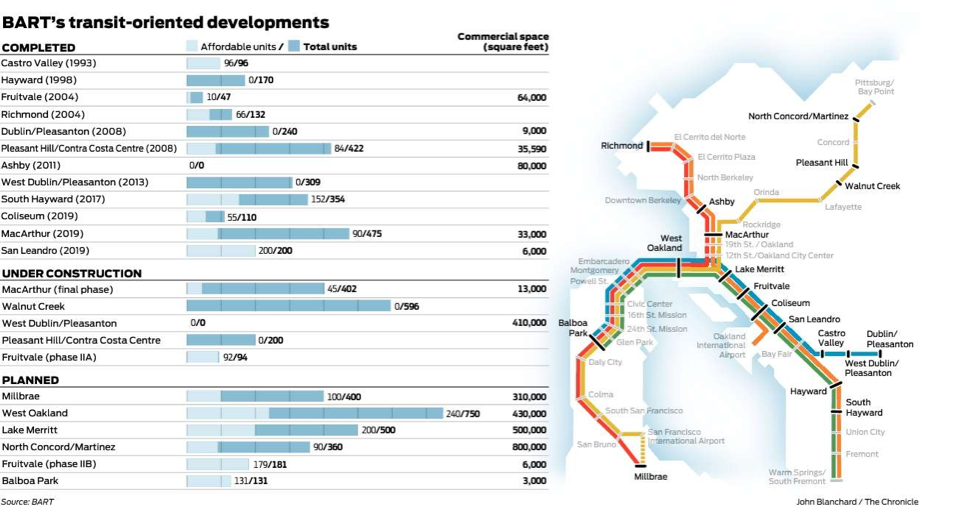

BARTs transit-oriented development is an example of urban infill in the Bay Area. With already 2500+ units developed near stations such as Dublin/Pleasanton and MacArthur, BART has filled 250 acres across 27 stations. The goal is to add up to 18,000 units by 2040 with 35% of the units reserved for below-market housing. Pairing economic diversity with transit-friendly locations is an instance of how to solve the climate crisis with housing.

Current policy needs to reduce the number of miles driven by at least 25% by finding better and more alternatives to cars for transport so as to stem the growth of super-commuters. This can include mass transit, access to walkable communities, and affordable housing near transit options. California Senator Scott Wiener introduced the More Homes Act, SB 50, that would have overridden local restrictive zoning and legalized small to midsize apartment buildings near job centers and public transportation. This bill, which would have set minimum affordability standards for some of those units, was defeated in January 2020. Contention surrounding the bill was that the legislation took too much power away from city and county governments and that it would have encouraged too much market-rate and luxury housing without assurances that there would be enough affordable housing for rent-burdened and low-income residents.

To address the equity concern of “who has the privilege of living where?”, Senator Scott Wiener recently introduced this March SB 902, which would allow construction of duplex, triplex, and four-plex residential units without additional local government approval in single-family neighborhoods. The bill does not change local control over size and shape of the housing that would be built but does superseded local zoning rules with limited density to create a baseline zoning for the state. Interestingly, these zoning efforts would be exempt from additional review under the California Environmental Quality Act.

MacArthur BART Station in Oakland

What's next?

Overall, housing and transit policy is largely controlled by city and state governments, so we need to build more momentum for housing near transit and jobs. The grass roots Yes in My Back Yard (YIMBY) movement indicates surging interest in housing and transportation issues, specifically that building more housing is a way to make cities more equitable and just.

Additionally, the state needs more policy solutions that expand upon transit-oriented development! Such solutions could reach across various scales that examine the intersection of land use, housing, transportation investments and travel choices as well as focus on infill development control policies to reduce the number of commuters crossing regional boundaries. The housing gap must be met at the local level, where communities determine the size of the housing gap and map housing hot spots. Cities need tailored and local policy to craft solutions depending on urban density, transit viability, and the unit potential on vacant parcels of land. Ultimately, creating this momentum to enable policy solutions will enable solutions that address both the future of the housing and the climate movement.

Pleasant Hill BART Station in Walnut Creek

References

Anzilotti, Eillie. (Aug 2017). California's Housing Crisis And Long Commutes Are Slowing Its Progress on Climate. Fast Company.

Badger, Emily. (Dec 2011). The Missing Link of Climate Change: Single-Family Suburban Homes. CITYLAB. Bloomberg.

Baldassari, Erin. (Jan 2020). Closely Watched California Housing Bill SB 50 Now Officially Dead. KQED.

Baldassari, Erin. (Sep 2019). Bay Area super-commuting growing: Here’s where it’s the worst. The Mercury News.

Barboza, Tony & Lange, Julian H. (July 2018). California hit its climate goal early – but its biggest source of pollution keeps rising. Los Angeles Times.

California Air Resources Board. (Nov 2018). 2018 Progress Report: California’s Sustainable Communities and Climate Protection Act. California Air Resources Board.

GHG Current California Emission Inventory Data. (2019). California Air Resources Board.

Jones, Christopher M., Wheeler, Stephen M., & Kammen, Daniel M. (Oct 2017). Carbon Footprint Planning: Quantifying Local and State Mitigation Opportunities for 700 California Cities. Cogitatio Urban Planning. 3(2):35-51.

King, John. (July 2019). At home at BART. San Francisco Chronicle.

Krieger, Lisa M. (Sep 2018). Curious About Carbon Emissions? Here's How Bay Area Cities Stack Up. Govtech.

Matier, Phillip & Ross, Andrew. (Dec 2018). Hard to cut down on auto emissions when commuters travel longer distances. San Francisco Chronicle.

McKinsey Global Institute. (Oct 2016). A Tool Kit to Close California's Housing Gap: 3.5 Million Homes by 2025. McKinsey & Company.

Schuetz, Jenny. (Jan 2019). To save the planet, the Green New Deal needs to improve urban land use. Brookings.

Semuels, Alana. (July 2017). From ‘Not in My Backyard’ to ‘Yes in My Backyard’. The Atlantic.

Wiener, Scott & Kammen, Daniel. (March 2019). Why Housing Policy is Climate Policy. The New York Times.

Yglesias, Matthew. (Dec 2018). Gavin Newsom promised to fix California’s housing crisis. Here’s a bill that would do it. Vox.